We Should Not Declare Victory Prematurely: Fight Against COVID-19 at Cook County Jail is Far From Over

Following a recent report from the CDC that the Cook County Jail has been successful in containing the COVID-19 outbreak within its walls, Cook County Sheriff Tom Dart was quick to tell the Chicago Tribune on Tuesday that he responded in the “quickest and most massive way.” Appearing before the Cook County Board of Commissioners for a budget hearing, Dart told the Board – as they commended him and his staff for the recent CDC report – that he was responsive on “day one” of the COVID-19 pandemic, emphasizing his alleged “cutting edge” response to the virus. This response, he argued, spoke directly to the Sheriff’s need for a budget increase. Dart claims he needs more money to ensure necessary protocols remain in place.

Dart’s pleas for increased funding were directly tied to the CDC report of containment and to his claim that the Sheriff’s Office, with his leadership alone, was responsible for controlling COVID-19 spread in Cook County Jail. However, Dart’s declaration belies a lengthy period of nonresponse from his office at the beginning of April. A major reason the pandemic’s impact in the jail slowed, or plateaued, was because of the measures Dart was court-ordered to implement, not the actions he took on his own. As we evaluate the Cook County Sheriff’s Office (CCSO) in its effectiveness controlling the pandemic, and look toward the future, it is important to understand the critical role played by the United States Federal District Court, attorneys for the plaintiffs, and the people who themselves are detained in Cook County Jail.

In the first half of April, the Cook County Jail was rapidly becoming a disastrous nexus for COVID-19 infections. On April 3, Anthony Mays and Kenneth Foster sued the Sheriff, on behalf of themselves and others similarly situated, because of Sheriff Dart’s failure to respond to the unique risks the virus posed to those forced to live in the jail (Mays et al. v. Dart). Throughout April, both detained individuals and jail staff alike reported insufficient access to soap, hand sanitizer, and face masks; improvised cloth face masks were being confiscated. People were made to sleep in beds that were just two-to-four feet apart, many in dormitory-style housing where dozens shared a single room. At intake, individuals were held in “bullpens,” where multiple people are detained together for extended periods in a single cell. Jail staff were not regularly sanitizing common area surfaces or providing materials for the detainees to do this themselves.

Although Sheriff Dart vociferously disputed the claims from detainees and jail staff, dozens of affidavits were filed throughout the lawsuit by currently-incarcerated people, recently-released individuals, lawyers, and former medical staff at the jail confirming that conditions at Cook County Jail were, in fact, dire. Public defenders and private lawyers filed over 2,300 emergency bond hearings between March 23 and April 22 seeking their clients’ release from the jail because of worries over the spread of COVID-19.

Ultimately, Federal Judge Kennelly agreed with the plaintiffs’ requests for increased protections in the jail, and ordered Sheriff Dart to implement social distancing, provide more face-masks, and increase sanitation. The Judge issued a temporary restraining order that allowed the Federal Court to monitor compliance with the order, which went into effect on April 12. The Court extended that order on April 27 and it became a preliminary injunction. That injunction is still in place today, and Cook County Jail is still being monitored by the Federal Courts to make sure conditions remain safe. When Judge Kennelly extended the preliminary injunction over Dart’s objection on May 29, he made clear why: “The Sheriff did not voluntarily take all of the coronavirus-protective measures that he cites. Some were done pursuant to court order – either the TRO, or the preliminary injunction, or both. Judge Kennelly expressed concern that lifting the injunction would result in decreased protections:

Staying the injunction would permit the Sheriff to lift measures and thereby again place the health of detained persons at serious risk. That risk cannot be discounted based on the Sheriff’s assurances alone. Again, a number of the measures he took were instituted only after the Court’s TRO or preliminary injunction.

The Court found there to be a likely risk of substantial injury to detained persons if the order was lifted. Sheriff Dart’s own judgment and leadership were insufficient to offer a modicum of safety for detained individuals.

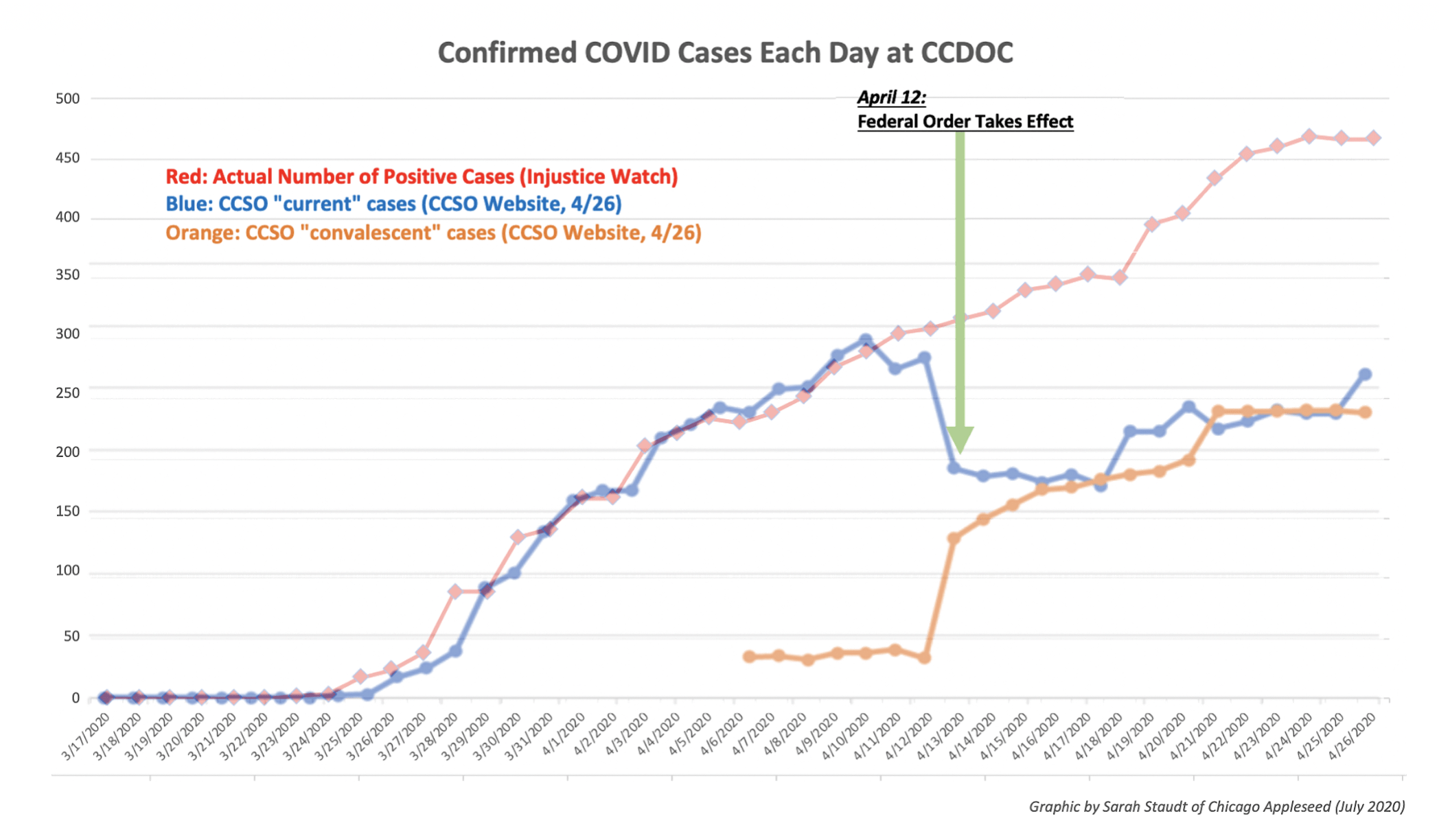

It is worth noting that in mid-April, the CCSO began to report COVID infection numbers differently, removing from the total count those people whom jail staff deemed “convalescent.” This classification, of course, is totally dissimilar to the way states, cities, or other congregate settings have counted total COVID cases since the beginning: the reported case count is usually the aggregate number of total positive tests, not the number of people currently exhibiting symptoms. By changing his definition, Dart was able to create a graph suggesting that COVID-19 cases were actually falling in mid-April, which, of course, was not the case. And although Dart claims to have instituted widespread testing in early April, his own numbers show that only about 10% of the jail population had been tested on April 15.

Because the CCSO still reports only the number of people who have tested positive who are currently in custody, not the overall number of positive tests or individuals over the course of the pandemic – it remains difficult, or impossible, for outsiders to get a sense of the true impact the COVID infection has had in the jail. Nonetheless, a study published in the Journal of Health Affairs found that Cook County Jail was associated with almost 16% of all documented COVID-19 cases in both Chicago and in Illinois through mid-April.

After the Sheriff was ordered by the court to institute social distancing, PPE, and sanitation, the rate of new cases in the jail finally began to plateau. Though the Sheriff credits himself, the fact is that the spread of COVID-19 was brought relatively under control because of the hard work of everyone involved: the CCSO staff, the lawyers who initiated the suit, and the jailed individuals themselves – who all provided vital information about conditions and were instrumental in encouraging PPE use, social distancing, and sanitation among their peers – and efforts by activists whose advocacy successfully dropped the total jail population by over 1,000 people between the end of March and the beginning of May.

As explained by Alexa Van Brunt, an attorney representing the plaintiffs, on WTTW:

This idea of ‘credit’ is just very telling about where the Sheriff’s head is, which is not the protection of humans, but the protection of his reputation…[and ignores] the plight of the many hundreds of detainees who were suffering inside the jail and are still suffering as a result of what the jail failed to do to protect them.

Sheriff Dart’s attempts to rewrite history reveals important lessons as we monitor COVID-19 in the jail going forward. Many epidemiologists agree that a major surge of COVID-19 infections is likely to return this fall. When it does, the Cook County Jail has the potential to, again, become an extremely dangerous hotspot – but, now, the jail’s population is even higher than it was on April 1. Social distancing in compliance with the Federal Court order was not even possible until late-April, when the jail population had finally been reduced by hundreds of people.

We need to remain vigilant in paying attention to the conditions experienced by those inside the jail, and closely monitor compliance with court orders regarding social distancing, PPE, and sanitation. Cook County will also need to significantly shrink the jail population. Contrary to Sheriff Dart’s claims at the budget hearing, most people detained in Cook County Jail pose no threat to society. Chicago Appleseed obtained, via FOIA request from the CCSO, a roster of the jail population on June 30, including all charges against each detainee and their bonds on all cases. Over 1,500 people are charged with non-forcible felonies; over 500 are incarcerated solely because they cannot post a bond of $10,000 or less. It is important that the criminal courts move quickly to review and resolve cases wherever they can to stop the jail population from continuing to climb.

Chicago Appleseed and the Chicago Council of Lawyers commend the efforts of the legal team from Loevy and Loevy and the MacArthur Justice Center at Northwestern University in holding Sheriff Dart accountable for controlling COVID-19 within the Cook County Jail. We also commend the thousands of people living in the jail, the CCSO staff, defense lawyers, State’s Attorneys, volunteers, protestors, and others, who not only revealed the dangerous conditions in the Cook County Jail, but also worked hard to save lives. We are honored to remain a partner in this effort for as long as COVID-19 remains a threat.

We should not declare victory prematurely – the fight against COVID-19 in pretrial detention is far from over.

Sarah Staudt is Chicago Appleseed & Chicago Council of Lawyers’ Senior Policy Analyst & Staff Attorney, working on issues of criminal justice in Cook County and throughout Illinois.

Kaitlyn Filip is an Appleseed Network/Collaboration for Justice Fellow and a JD-PhD Student at Northwestern University’s Pritzker School of Law, studying Communication Studies: Rhetoric and Public Culture.