Checking on the Cook County Criminal Court’s Case Backlog

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, Chicago Appleseed Center for Fair Courts has been tracking the status of Illinois Courts’ shutdown.

With COVID-19 causing the courts to shut down and the Illinois Supreme Court to pause speedy trial rights, case processing slowed to a crawl. In April, Injustice Watch reported that more than 33,600 felony cases were pending in Cook County, which was a 22% increase from the same time last year. According to documents obtained through open records requests, the rate of felony cases closed per felony cases arraigned — which can be seen as a basic measure of how efficient the courts are at resolving cases — was half the target rate set by the Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office (CCSAO) for 2020 (the target rate was 1.4 cases closed for every one open, but the actual rate was 0.7 cases closed per one opened). This deficit means that the courts have needed to play catch up as pandemic restrictions have been lifted.

While some progress has been made in clearing the court backlog, it is essential that the Cook County Courts keep doing the hard work to resolve these cases fairly and quickly. Three months ago, more than 2,600 people had been sitting in the Cook County Jail or on EM for longer than a year waiting for their cases to resolve. When speedy trial rights are restored on October 1, we can expect many of those people to demand trial as soon as they are given the opportunity — generally, case preparations by lawyers have continued during the pandemic even though the courts have been slow to hold trials. The courts could easily become overwhelmed in October if many people exercise their constitutional rights at the same time, as they have every right to do. The Court will need to continue to accelerate resolutions so that as few cases as possible are pending on the day speedy trial rights resume.

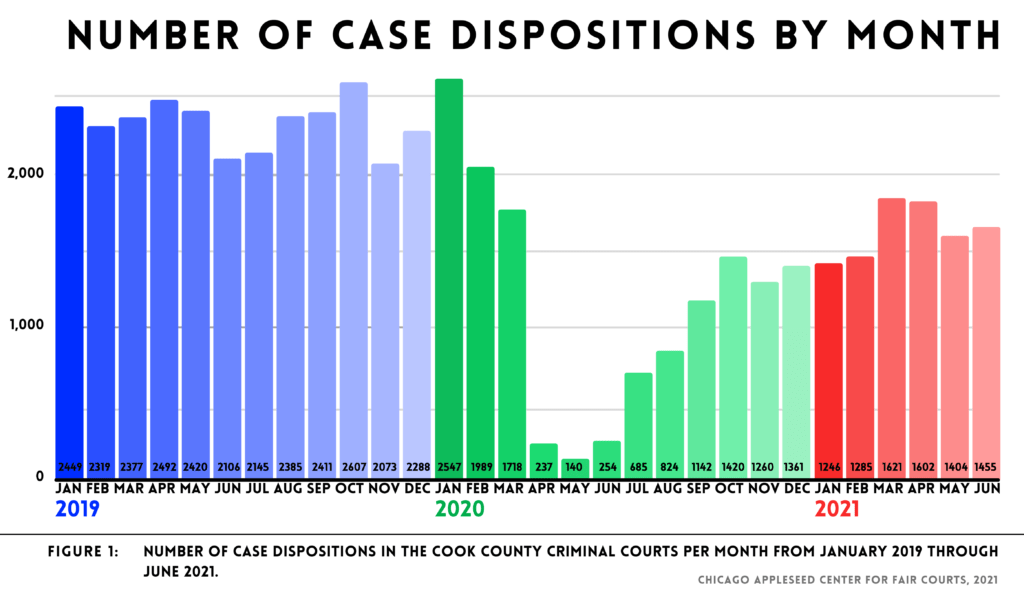

Progress on addressing the backlog was slow in early 2021, but recent data from the CCSAO since March shows that resolution rates have been at slightly higher levels — and well above where they were one year ago. This is an encouraging pattern; however, the courts will need to continue to accelerate the rate of case resolution to account for both the case backlog and for new cases coming into the system.

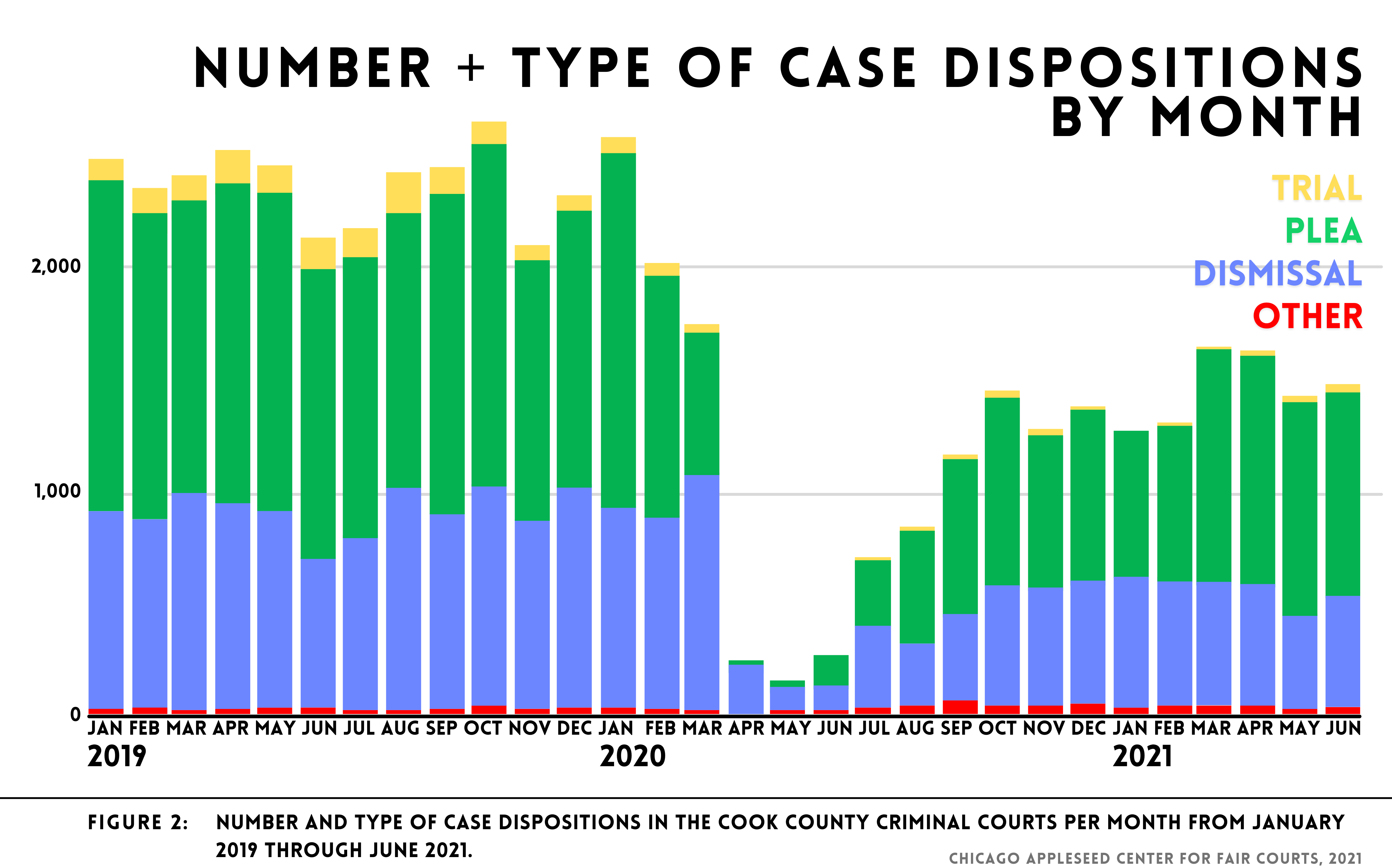

In general, the rate of monthly case dispositions has recovered to rates that are lower than the rates in 2019, but substantially higher than the rates in the middle of the pandemic.

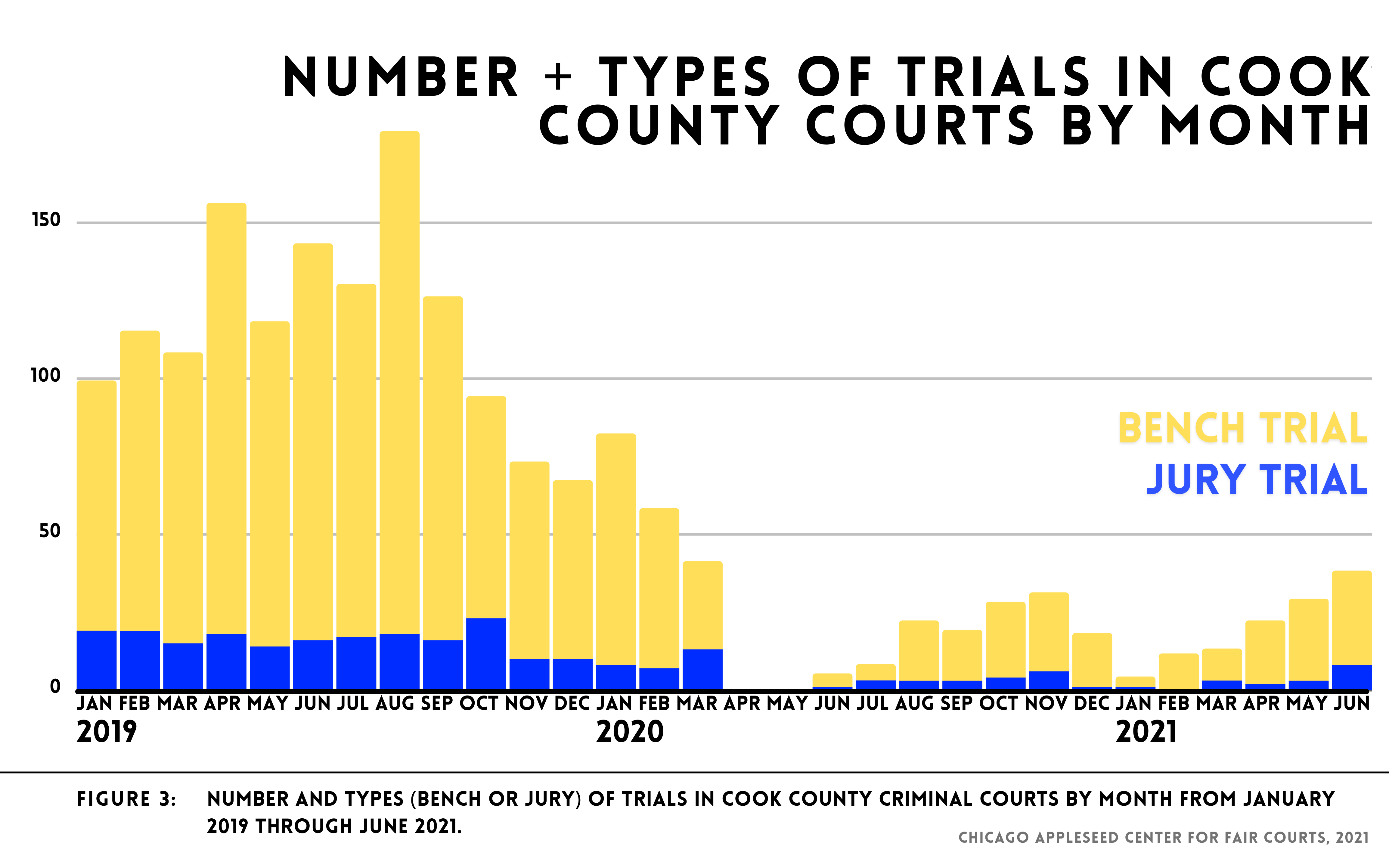

These gains have been seen among all kinds of case resolutions — trials, guilty pleas, and case dismissals (see Figure 1: Number of Case Dispositions by Month). Most cases are resolved through dismissal or plea, and all types of resolutions make up at least some of the recently increased resolution rate (see Figure 2: Number and Type of Case Dispositions by Month). Of all possible case dispositions, trials have been a particular area of interest since the reinstatement of speedy trial rights will most acutely affect cases bound for trial. Unfortunately, trials have not recovered at the same rates as guilty pleas and case dismissals. Jury trials, in particular, have been occurring less than half as often as they did in 2019 (see Figure 3: Number and Types of Trials in Cook County Courts by Month).

Cook County State’s Attorney Kim Foxx has stated that her office will prioritize “violent” cases when choosing where to first pursue quick trials — and will likely dismiss many lower level, non-violent cases. This is sound policy for shrinking the backlog and should be pursued fully as soon as possible. As noted above, Chicago Appleseed and other local legal advocacy and community-based groups have been openly concerned about the state of the Cook County Court’s backlog since the beginning of the pandemic. In September 2020, we found public data showing in a “normal” year, the Cook County Criminal Courts enter an average of 6,966 case dispositions between April 1 and June 30. This number includes dismissals, guilty pleas, and trials. In 2020, the courts resolved only 477 cases — about 7% of the usual total. Then, in January, our analysis of the case backlog in the Criminal Division of the Cook County Circuit Court showed that people (both those accused of and harmed by crime) are waiting increasingly long periods of time for justice: at least 40 people charged with misdemeanors and almost 500 charged with Class 4 felonies (such as drug possession, driving on a revoked license, or theft, for example) had been in the Cook County Jail or under electronic surveillance for over six months due to the shutdown.

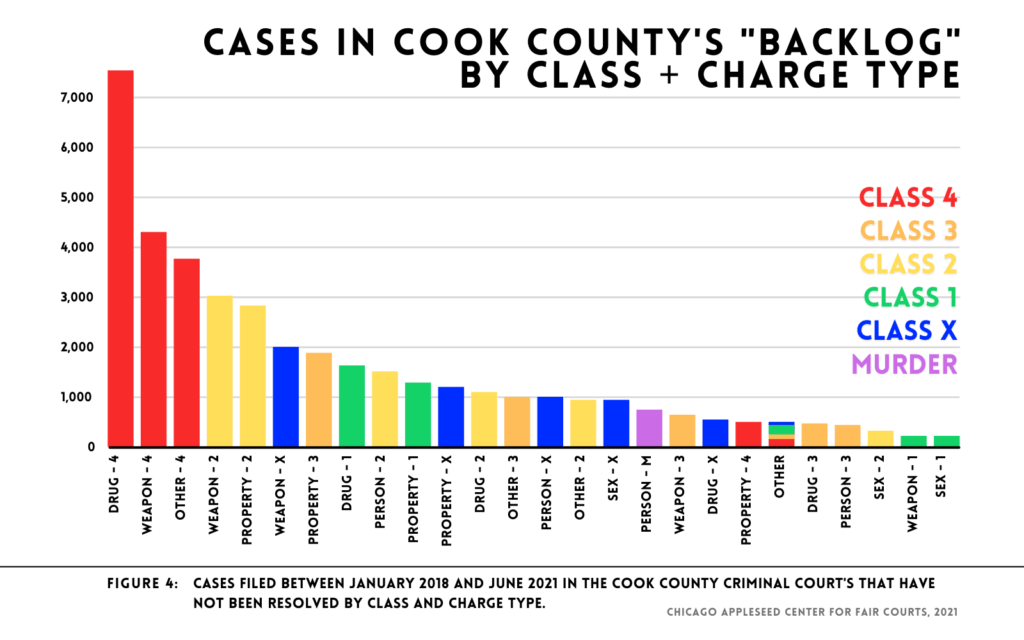

Currently, the backlog consists primarily of lower level cases.

Over 10,000 cases are either Class 4 drug cases or Class 4 traffic cases; many weapons cases have been pending for over a year (see Figure 4: Cases in Cook County’s “Backlog” by Class and Charge Type). Traffic cases make up the largest part of the uncategorized “other” category shown on Figure 4; there are 3,062 Class 4 traffic cases on the graph — mostly DUIs and driving on suspended license cases. These cases could easily be resolved, dismissed, deferred from prosecution, or reduced to misdemeanor charges while speedy trial rights are still suspended. However, if these cases continue to linger in the system after October 1, there is a risk that people will demand trial, which will add to the rush of cases set for the fall.

Fundamentally, there are three ways the CCSAO can “de-prioritize” cases for prosecution. The first is to dismiss the cases outright. This solution is just and appropriate for many cases where people have been living under the threat of prosecution, often while complying with onerous pretrial conditions for long periods of time during the pandemic. The second and third solutions, respectively, are to use diversion and deferred prosecution programs or to offer guilty plea deals that are favorable to defendants (those that avoid felony convictions and prison time). All of these solutions, especially the first, should be used liberally to reduce the backlog.

(1) Review all drug, traffic, and other low-level cases for possible dismissal — particularly those that went through Cook County Branch Courts between March and December 2020.

The trauma of going through the criminal court process is punishment in and of itself. It stands to reason that because case processing times have grown longer during the pandemic, people charged with crimes have experienced an undue level of punishment, surveillance, and restrictions from our pretrial system than would normally be the case. Thousands of people have been subject to pretrial electronic monitoring, curfews, mandatory check-ins, and other surveillance during this time. In 2020, the Office of the Chief Judge’s electronic monitoring program installed 1,380 new GPS and 268 new radiofrequency monitors (usually used to monitor curfews), and had an average of 7,917 people on pretrial supervision each day. These almost 8,000 people are in addition to the over 3,500 other people per day who have been incarcerated in their homes under the Cook County Sheriff’s electronic monitoring program. The stated goals of sentencing (punishment, incapacitation, rehabilitation, and deterrence) have surely already been achieved for this group of people, who have had their lives monitored and restricted for over a year in the midst of a global pandemic that already caused immense suffering.

In a normal year, the Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office dismisses about 65% of Class 4 drug cases; most of those (81%) are dismissed outright without going through a diversion program. These dismissals have slowed during the pandemic, along with deferred prosecution referrals. While State’s Attorney Foxx has consistently stated that her office will de-prioritize the prosecution of these cases. To do so, they must offer dismissals and deferred prosecution to a large number people with Class 4 cases that were filed during the pandemic — not simply those filed now that the courts are mostly back up and running at full capacity. One customary reason for dismissal of drug and traffic cases, particularly in the Branch Courts, is the failure of the arresting officer to physically appear in court for the first court date — in many cases, judges will deny a State’s Attorney’s request for a continuance in those circumstances. Cook County Public Defenders have told Chicago Appleseed staff that during the pandemic, because no one was physically appearing in court, State’s Attorneys more often sought and were granted continuances on preliminary hearings, increasing the number of active prosecutions for low-level drug possession.

The best place to look for drug cases that may be easy to dismiss by agreement is in the felony trial rooms throughout Cook County. The proportion of total dismissals that occurred in the Chicago-area Branch Courts dropped substantially during the pandemic. During 2019, 62% of felony case dispositions occurred in the Branch Courts and essentially all (98.6%) dispositions that occurred there were dismissals. During the pandemic, from March 2020 through December 2020, only 25% of dispositions occurred in the Chicago Branch Courts. This rate has recovered extremely well — to 68% of dispositions — but the cases that were not disposed of in Branch Courts during the pandemic are now at the Criminal Courthouse at 26th Street in Chicago, where State’s Attorneys and judges may be less inclined to dismissing low-level cases. Judges should consider this fact when looking at drug, traffic, and other cases that are in their felony courtrooms.

(2) Review the backlog of cases for referrals to the Drug Deferred Prosecution Program (DDPP) and other diversion programs.

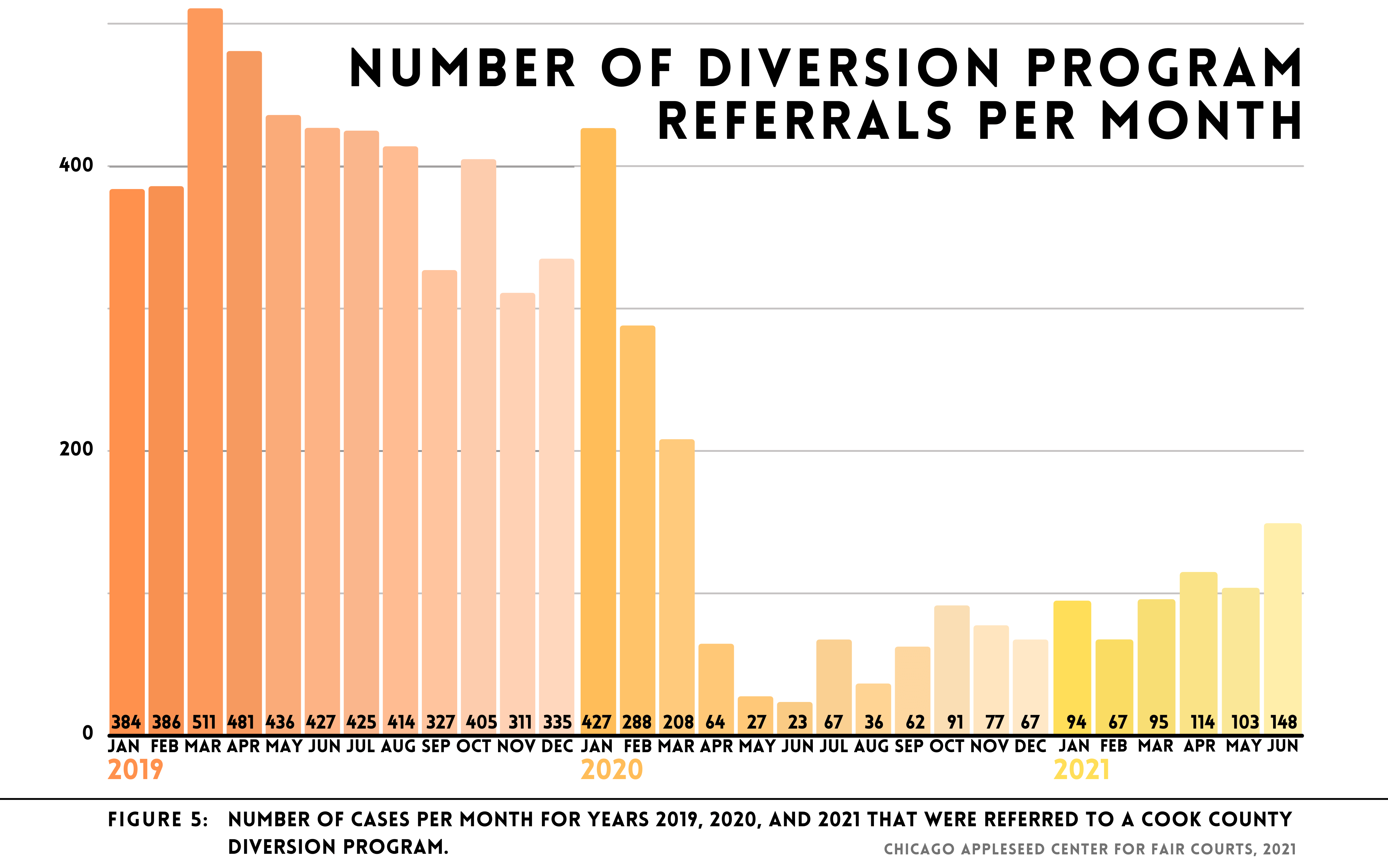

About 28% of all cases currently in the backlog are drug cases. Many drug cases are eligible for diversion — another feature of the legal system that has been underutilized during the pandemic. Unlike other kinds of resolutions, referrals to diversion programs have not increased substantially in 2021, and remain well below their pre-pandemic levels. While overall monthly dispositions are currently at about two-thirds of their 2019 levels, referrals to diversion programs remain at about one-third of their 2019 rates (see Figure 5: Number of Diversion Program Referrals per Month).

The major drop in referrals is due to underuse of the most commonly used diversion program, the Drug Deferred Prosecution Program (DDPP), which accounted for 48% of all diversion referrals (over 2,300 cases) in 2019. So far in 2021, the DDPP accounts for only 9% of referrals although all other diversion programs have rebounded to their pre-pandemic levels. Approximately 11,000 drug felonies filed since January 1, 2019 have not been resolved. The DDPP is a simple diversion program that requires people charged with drug cases to be evaluated for drug treatment at community-based organizations, and then present proof that they have done so to get their case dismissed. Normally, the program is available primarily for Class 4 drug possession cases for people with little to no felony background; under these circumstances, however, it should be expanded to include higher level cases. This would require few court resources — the Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office must simply screen the large number of cases that were filed during the time that evaluations for diversion were not being conducted. Everyone who has had their case pending during the pandemic has experienced an undue level of pretrial punishment already, as discussed above.

(3) Offer reasonable, no-prison plea deals for individuals who have already served their time or who are charged with low-level offenses that cannot be diverted or dismissed.

Every person facing an accusation deserves their day in court — if they want it. However, State’s Attorney Foxx has expressed her commitment to offering reasonable, favorable plea deals and dismissals to people who do not pose any threat to the community. Prosecutors and judges can help lessen the backlog by offering pleas that defendants are likely to accept and by committing to consistently proposing only the lowest available sentence for each accusation. For individuals without prior felony convictions, any deal that allows the continuation of a clean record should be used as frequently as possible.

One obvious area where this approach can be used is the large number of Class 4 gun possession cases that are pending in the courts. Since 2017, most people facing Class 4 gun possession receive less than the minimum sentence (one year in prison): about 34% receive probation, 24% are sentenced to a year inside, and 22% have their cases dismissed altogether. Only 13% of people receive a sentence longer than one year. While most Class 4 gun cases are non-probationable, the First Time Weapon Offender Program (730 ILCS 5/5-6-3.6) creates an exception (a potentially expungeable form of probation) for people under 21 years old. State’s Attorney Foxx’s administration has already made frequent use of this provision and should continue to do so.

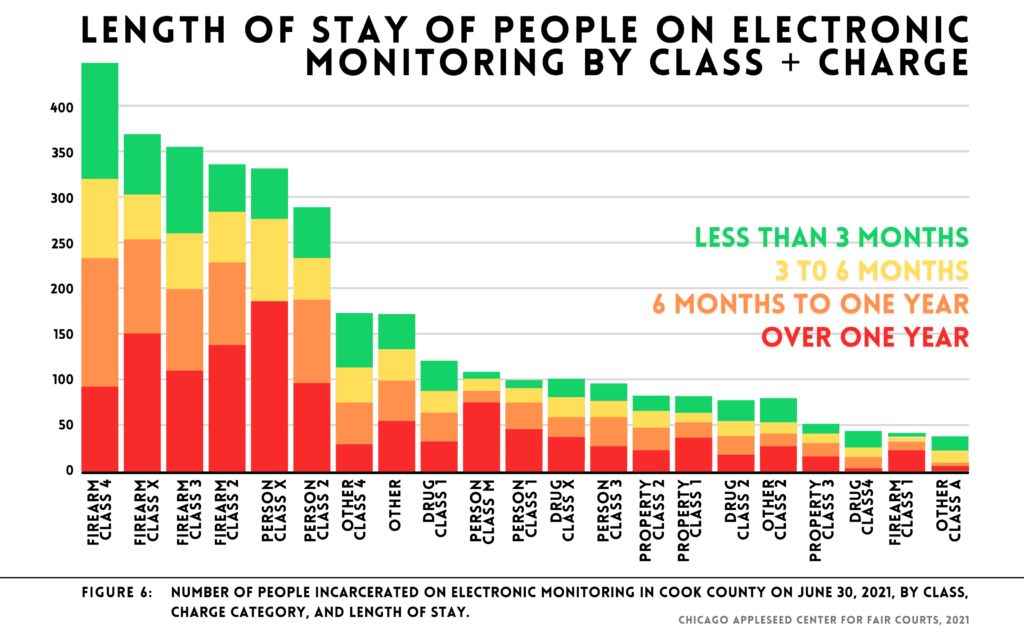

There are currently about 966 young adults under the age of 21 charged with a Class 4 gun possession felony as their highest offense. Not all of them will be eligible for the program, but many are. All of these young people should be considered first for dismissal and then for the probation program as a way to resolve their cases in a more effective and humane way than by incarceration. There is an overlapping set of people with gun charges who may or may not be eligible for the First Time Weapon Offender program, but have been incarcerated in jail or on electronic monitoring for so long that they would not receive prison time even if sentenced to the lowest end of their sentencing range, because of their time-considered-served credit. There are a total of 679 people on electronic monitoring (see Figure 6: Length of Stay of People on Electronic Monitoring by Class and Charge) and 330 people in the Cook County Jail who have booking dates that suggest they have likely already served time equivalent to the minimum sentence possible should they be convicted.

The urgency of clearing the criminal court backlog may have increased now that there is a firm deadline by which speedy trial rights are restored on October 1 — but any further delay of these rights should only be considered a failure of the Cook County Courts to effectively maintain people’s basic constitutional protections.

Not only did the courts return to work at a much slower pace than other parts of the government and other industries, but the fact that people in jail will still be forced to wait for access to their constitutional rights while Chicagoans enjoy beaches, bars, and restaurants is a sad commentary on the way our society has prioritized some individuals’ human and civil rights over others’ during the pandemic. Still, the October resumption of the right to a speedy trial gives some light at the end of the tunnel to people who have been waiting for their day in court.