Prison Reform Advocates Call to End Civil Commitment in Illinois

A new report from the Prison Policy Initiative (PPI) focusing on U.S. systems of confinement calls for the end of civil commitment. Chicago Appleseed Center for Fair Courts supports this call.

In Illinois, for example, the Department of Corrections (DOC) facilities are overseen by the John Howard Association, an independent prison watchdog organization. But Rushville Treatment and Detention Facility, a civil commitment center that opened after Illinois enacted its own Sexually Violent Persons Commitment Act in 1998, is not subject to the same kind of oversight because it is housed under the Department of Human Services and is not technically classified as a prison.

Prison Policy Initiative (2023)

Civil commitment is the practice of indefinitely detaining people upon release from prison after they have completed sentences for criminal “sex offenses” in 20 states and with the Federal Bureau of Prisons. This is possible under “Sexually Violent Persons” legislation, whereby people who are about to be released from incarceration are screened for “likelihood of committing future sexual offenses.” When the result of that screening is “substantially probable,” they land in “legally and ethically dubious” civil commitment facilities — sometimes called “shadow prisons” — likely indefinitely.

Illinois has one of the highest populations of these so-called “shadow prisons,” civilly committing at least 525 people in 2022.

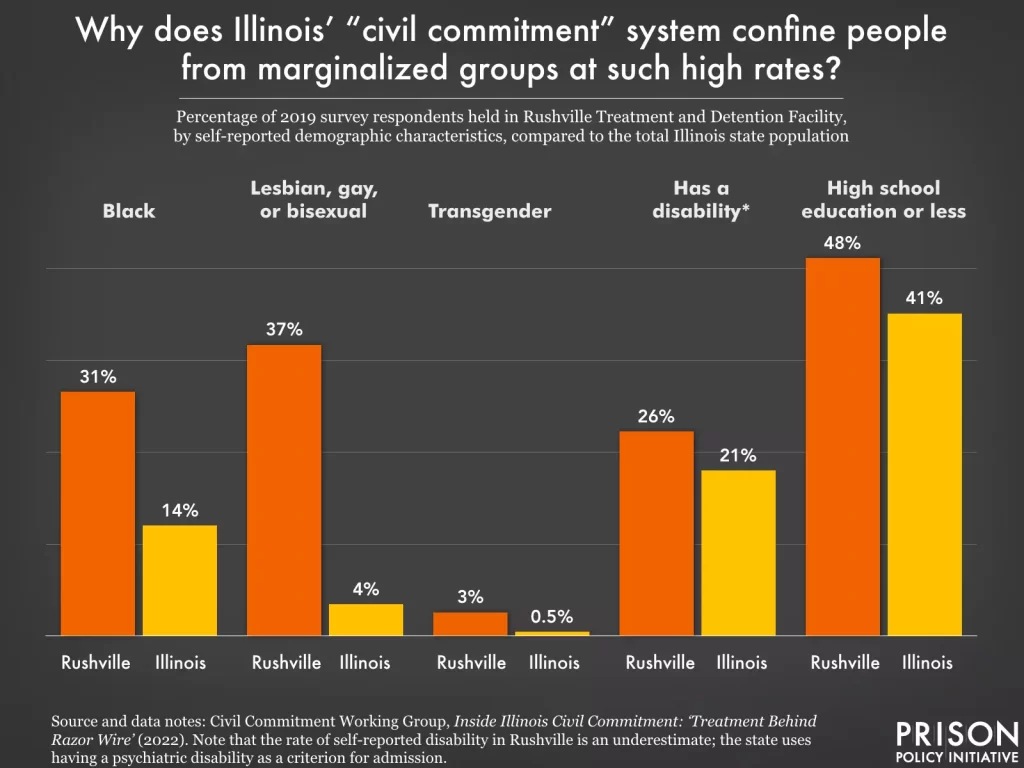

A report published at the end of 2022 exposed “demographic disparities, discrimination and abuses,” while showing that being civilly committed to Illinois’ Rushville Treatment and Detention Facility is almost always a life sentence; between its opening in 2006 and 2020, more people at Rushville died than were discharged. Unsurprisingly, Black people are incarcerated in civil commitment facilities at twice the rate of White people.

Prison Policy Initiative critiqued several red flags related to civil commitment practices, such as due process violations, the lack of accountability, questionable treatment practices, and inexperienced staff with punitive attitudes.

- Due process violations. Subjecting people to enduring sentences of detention after release from prison until they can prove they “are no longer a danger” violates due process rights. The system is described as “pre-crime preventative detention” because it aims to thwart a potential future act that has not occurred on the basis of discriminatory risk assessment tools (RATs).

By the logic of civil commitment, 100% of people inside have a psychiatric disability. In the Illinois report, 26% of Rushville respondents self-identified as having a disability, compared with 21% of the Illinois population. Low levels of educational attainment (i.e., having a high school degree or less) were also very high, at 48%.

Prison Policy Initiative (2023)

- Lack of accountability. Since these facilities are not operated by the Department of Corrections, they are subject to different reporting requirements, which makes it difficult or impossible to gather data and hold the institutions accountable.

- Questionable treatment practices. If detainees ever want to “complete” treatment — a requirement for leaving the civil commitment facility — they must participate in questionable treatment practices. The system holds itself up on the premise of providing “treatment,” but at least in Illinois, that “treatment” looks more like a series of mandatory recountings of every traumatic sexual experience they’ve ever had (without therapist-patient confidentiality), pseudoscientific risk assessments/evaluation tools like polygraphs and penile plethysmographs, and potential chemical castration. This “treatment” is consequently disavowed by the American Psychiatric Association.

- Staffing concerns. “Rotating cast of inexperienced medical staff,” often including graduate students and interns, determine the detained individual’s “progress” and eligibility for release. Previous contractors to these facilities described facing intense pushback from staff and administrators when they tried to advocate for conditional release of people in the facilities.

Therefore, advocates are calling for an end to civil commitment upon release from prison, urging greater reliance on “initiatives that actually prevent child abuse and sexual violence, including measures advancing economic justice, accessible non-carceral mental healthcare, comprehensive sex education, and consensual, community-based restorative and transformative justice initiatives.”