Judicial Discretion in Cook County’s Problem-Solving Courts

Cook County’s problem-solving courts (PSCs) are specialized diversion courts that work with accused people whose mental health conditions and/or substance usage may have contributed to their arrests. The PSCs include Drug Treatment Courts, Veterans Treatment Courts, and Mental Health Courts; in other words, each type of PSC has a different target audience, all with the purported goal of rehabilitating individuals who meet the criteria for entry.

The Cook County PSCs have achieved some success in providing alternatives to incarceration. However, the research of the Collaboration for Justice of Chicago Appleseed Center for Fair Courts and the Chicago Council of Lawyers has recently raised concerns about some aspects of the PSCs that need to be addressed.

One issue of note are the low overall graduation rates of the PSCs and the especially low graduation rates of many individual courtrooms. The large variance in graduation rates across problem-solving courtrooms highlights the role of judicial discretion as an influence on success rates. Judges in PSCs hold significant discretion in determining the practices in their courtrooms, which ultimately affects participants’ outcomes.

Here, we discuss the scope and impact of judicial discretion in these specialty courts and why it deserves attention.

Varying Graduation Rates

Cook County has 21 post-plea PSCs, which are categorized as Drug Treatment Courts (DTCs), Mental Health Courts (MHCs), or Veterans Treatment Courts (VTCs). The seven DTCs deal with accused people who use substances, the eight MHCs involve people with mental health concerns, and the six VTCs serve United States Veterans involved in the criminal legal system. Each PSC has different qualifications for entry, but generally, people enter these courts after they have pled guilty to charges that a court has identified as related to one of the aforementioned conditions. A participant “graduates” from a PSC if the judge certifies that they have met the requirements for that PSC.

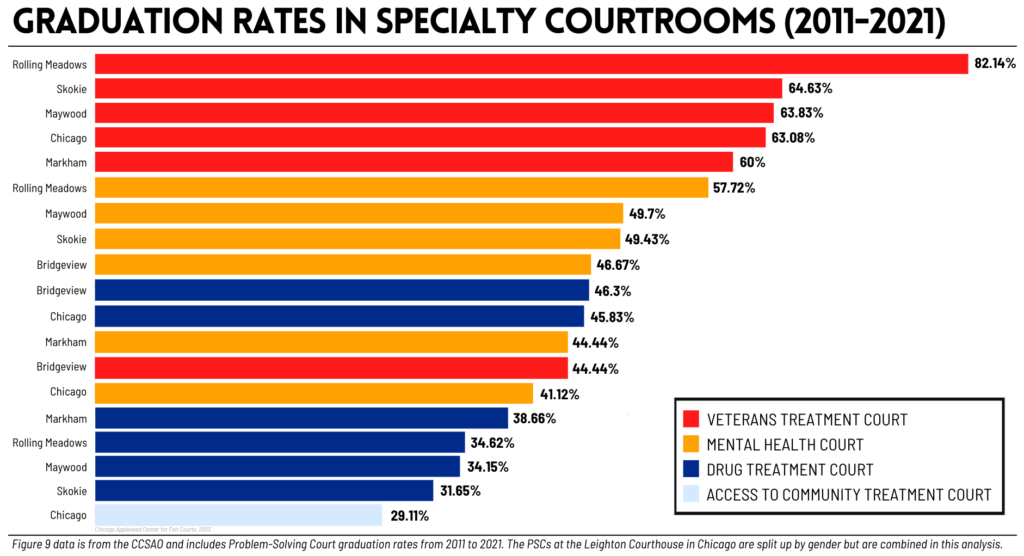

The overall combined completion rate of all programs is 55% [but] there are even wider variations in graduation rates when comparing individual courtrooms. In general, each courtroom has a different judge. Because the profiles of PSC participants are unlikely to change much between programs with the same focus and procedures, the wide variation in graduation rates may suggest that judges have different practices for how people are terminated from PSC programs and for what reasons. The result is that it can be an accident of geography whether someone is in a program that has a higher graduation rate or a lower one. For example, someone who qualifies for MHC in Cook County’s Rolling Meadows branch court enters a program where 58% of participants succeed, whereas a person who qualifies at Chicago’s felony courthouse enters a program where only 41% succeed (“One Size Doesn’t Fit All” – March 2023).

The overall graduation rate of the post-plea PSCs is quite low – around 55% – but graduation rates vary across each PSC type: For the DTCs, the average graduation rate is 42%, participants in the MHCs graduate at a rate of 47%, and the VTCs have the highest graduation rate at 61%.

The relatively low graduation rates of the PSCs is of special concern because failure to graduate from a PSC significantly impacts participants’ lives going forward. For these post-plea programs, those who fail to graduate must fulfill the remainder of their sentence starting from the time they were admitted to a PSC; regardless of the amount of time they spent enrolled in the PSC, that time does not count toward their sentence. Thus, such participants sometimes spend more time engaged in the criminal legal system than they would have if they did not enter the PSCs at all. The cost for “failure” includes having a conviction on your record, which then limits housing, employment, and educational opportunities as a result of restrictive Illinois statutes. This is especially concerning since people who are engaged in the criminal legal system tend to be from low-income, primarily Black neighborhoods, which are already disproportionately harmed by historically racist drug laws.

The Impact of a Judge

Important to note is our finding that even greater variation in graduation rates exists across the individual problem-solving courtrooms, which each have a different judge.

- The seven drug treatment courtrooms have the lowest skewing rates of graduation, ranging from just 29% in the Access to Community Treatment (ACT) Court to a high of 46% in the others.

- The county’s eight mental health courts range in graduation rates from 41% to 58%.

- The veterans treatment courts have the highest rates of success, ranging between 44% to 82% across different courtrooms.

This variance in rates of success suggests judicial discretion as a key factor contributing to many participants’ success or failure to graduate from the PSCs. Courtroom assignments are an accident of geography for most participants, and yet it could have dramatic consequences for their likelihood to graduate or face incarceration.

Judges in the PSCs have much greater discretion than they tend to have in traditional courts. First, judges have great control over participants’ treatment plans, the frequency of their drug testing, and even their personal lives. This generally enables the enforcement of abstinence-only policies, which counter many substance use best practices and include a very high level of surveillance of participants’ personal relationships and activities. Moreover, judges determine their own responses to participants’ violations of program guidelines and treatment plans, which in practice are often overly punitive: in some cases, judges have adjusted treatment plans or even relied on incarceration as sanctions.

Reframing the Role of a Specialty Court Judge

In recent decades, advocates for education reform and educational sociologists have shifted their focus from dropout rates as a broad concern to the systemic factors that often push particular students out of educational systems. This “push out” framework is useful for considering the roles that those in power in courtrooms play in the failure of many participants to graduate from PSCs. The wide range of graduation rates across individual courtrooms suggests that the decisions individual judges make regarding treatment plans and sanctions may, in fact, “push” certain participants out of the PSCs.

In our report, we presented recommendations for how PSC judges should approach their role as guided by public health best practices:

- Incarceration should be entirely avoided for PSC participants. As incarceration presents intense mental and physical health risks, especially to people with preexisting mental health concerns, no participant should be incarcerated before or during their participation in a PSC. In particular, judges should end their practice of using incarceration as a sanction for active participants who break their rules in a PSC.

- Judges should grant participants autonomy to determine their own treatment plans based on consultation with healthcare providers rather than court actors. They should ensure that participants have access to a variety of treatment options, such as medication-assisted treatment, 12-step programs, and harm reduction services. Treatment should serve a participant’s individual health needs and should never be used as punishment.

- Judges should, to the best of their ability, respect medical confidentiality. PSC participants should never be required to disclose confidential medical or treatment information to the court in order to participate in a PSC. In the Restorative Justice Community Courts (RJCC), another diversion program in the Circuit Court of Cook County, advocates successfully pushed for legislation (signed in 2021) that ensures information provided during RJCC processes “is privileged and cannot be referred to, used, or admitted in any civil, criminal, juvenile, or administrative proceeding unless the privilege is waived…by the party or parties protected by the privilege.”

Conclusion

Though the problem-solving courts in Cook County divert some participants from carceral outcomes and connect them with public health resources, the manner in which judges employ their great discretion pushes many participants out of the program and into the criminal legal system. The PSCs have a dangerously low overall graduation rate, and graduation rates across courtrooms vary significantly. Judicial discretion is not an inherently bad thing; as described above, discretion in certain problem-solving courtrooms (i.e., VTCs with 82% graduation rates) has clearly led to success for many participants. That said, discretion should be used as a mechanism of support – not of control, surveillance, or punishment. To the extent possible, judges should use their discretion to support participants and connect them with community-based resources, which are essential for individuals’ wellbeing.