NEW – Restorative Justice, Community, and the Courts: An Analysis of the Impact, Benefits, and Elements “Constantly in Conflict” in Chicago’s Restorative Justice Community Courts

Our new report examines the Circuit Court of Cook County’s three Restorative Justice Community Courts (RJCCs) located in the Avondale (North Side), Englewood (South Side), and North Lawndale (West Side) neighborhoods of Chicago. The North Lawndale court opened in 2017, and Englewood and Avondale followed in 2020. The RJCCs generally serve 18-to-26-year-olds living in or near the three target neighborhoods who are charged with nonviolent felonies and misdemeanors; they aim to divert these young people away from the traditional criminal court process, offering them the chance of having their cases dismissed without a conviction upon successful completion of the program. Our report is an exploratory study using data from interviews with stakeholders, court-watching observations, and data from the Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office (CCSAO) and Office of the Chief Judge (OCJ) to explore if and how the RJCCs’ practices align with and/or depart from general restorative justice best practices.

Restorative justice is a framework stemming from Indigenous beliefs focused on relationships as a foundation for collective wellbeing. When applied in contexts related to the criminal legal system, restorative justice offers a striking contrast to retributive and punitive models of justice. Instead of focusing on punishment and deterrence, restorative justice centers the needs of victims, the people who caused harm, and their communities, placing the decisions surrounding addressing harm in the hands of people who are directly impacted.

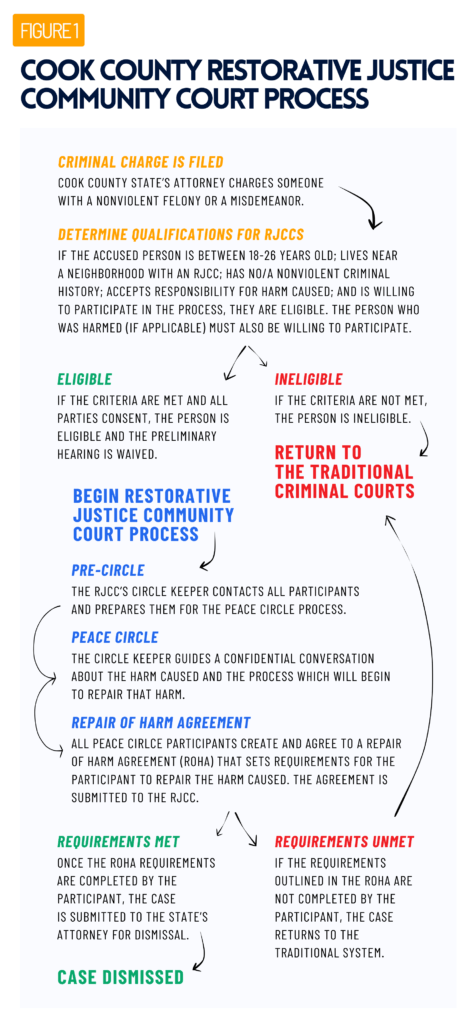

The first step to engage with the RJCCs is to be referred by the prosecuting attorney on one’s case. Next, a prospective participant would speak with a circle keeper, who meets with all relevant parties (the participant, the victim, and community members) to discuss the pathway to repair and create a Repair of Harm Agreement (ROHA). The ROHA outlines the goals that a participant must achieve in order to graduate from the program. While ROHAs are meant to be individualized documents, RJCC participant ROHAs seem to share common themes such as completing several hours of community service and sometimes meeting certain education/workforce requirements (such as obtaining a GED or finding a job). Participants must also attend regular RJCC court calls to check in on their ROHA progress. If the person completes the requirements in their ROHA, they “graduate” from the program and get their charges dismissed; if the participant “fails” the RJCC program, their case goes back to the Criminal Division and the traditional process resumes. Participants spend an average of 13 months in the program.

Our analysis of the CCSAO’s data shows 595 people entering the RJCCs between 2017 and 2023. According to the Office of the Chief Judge (OCJ), of the 100 people who were admitted into the program between 2020 through 2022 and had completed their time in the program as of March 31, 2023, 94% of people had their charges dropped or dismissed and 6% had been found guilty. Compared to Cook County’s post-plea problem-solving courts (in which participants are required to enter a guilty plea before participating) where only about half of participants tend to graduate, the Restorative Justice Community Courts seem to result in better outcomes for participants but also admit significantly fewer people.

In order to get the full picture of the culture and functioning of these courts, we interviewed 16 court stakeholders, community advocates, service providers, and former participants and collected 18 court observations by our volunteer court-watchers in addition to reviewing quantitative data. Generally, our findings show positive outcomes for people involved in the RJCCs who complete the program and “graduate,” but our research also uncovers some concerns related to the inherent tensions between restorative justice and retributive justice ideology (i.e., the traditional criminal legal system). Some of our key findings show:

- Only 7% of all cases that went through an RJCC included an identifiable victim. While a stated goal of the RJCCs is “to end the harmful cycle of revenge and recidivism,” the reality does not particularly encapsulate this—most of the cases do not address harm done to a victim or a community. Therefore the court process seems disconnected from fundamental restorative justice goals of building and repairing relationships. In the first two years of the RJCCs’ existence, the courts dealt almost exclusively with drug cases, which in the last two years have dropped to only 10% of cases; instead, gun possession cases now make up over 80% of cases in RJCCs. There’s no doubt that these cases should generally be diverted from traditional prosecution, but as one interviewee stated, both drug and gun possession cases are charges where the “State of Illinois” is the legal “victim,” in the case, which is “a harder way to begin this…process, because you dehumanize it.”

- The flexibility and recognition of participants’ humanity is greater in RJCCs than in traditional criminal proceedings in Cook County. Court actors appear to want the best outcomes for participants in the program and generally operate with a harm-reducing perspective. Our court-watchers observed participants being spoken to and handled in a way that communicates more respect and regard for their overall wellbeing in comparison to the traditional court process.

- At the same time, punishment and surveillance play a notable role in these courts; court actors routinely threaten to send participant’s cases “back to [the criminal courthouse at] 26th Street.” The tensions that exist from this program being housed within the criminal legal system loom large, as some of the more punitive practices and logics of that system are reproduced within the RJCCs.

- Court stakeholders, participants, and court-watchers all raised concerns about the appropriate use of participants’ time. At some courts, participants were routinely held at court calls for far longer than scheduled. Our court-watchers also noted a shortage of Circle Keepers that slowed down court processes. Additionally,interviewees noted that some Repair of Harm Agreement (ROHA) commitments would interfere with other personal and professional obligations and often appear to bear little relation to their purported offense (for example, requiring 80 hours of community service for gun possession cases). In developing these agreements, it should be considered whether the requirements are actually repairing harm or creating unnecessary barriers for participants to complete the program and disengage with the criminal legal system.

- Despite removing some of the aesthetics of a traditional courtroom by having stakeholders wear street clothes and organize seating in a non-hierarchical way, most of the power of the RJCC still rests with judges and prosecutors rather than communities. Our research uncovered minimal day-to-day community involvement in the RJCCs, which is concerning. Community fundamentally plays a central role in restorative justice. When community members are integrated into the process, restorative justice can empower communities, as opposed to institutions, to take control over resolution of its conflicts. This is not actualized in the RJCCs, where community members were rarely (if ever) present in court. Interviewees shared that community engagement will remain difficult unless the process includes an identifiable person or group harmed. One interviewee suggested that community participation has been hindered by lack of community power in the process: “I’ve been invited to too many circles where they wanted the community to sit in circle, but ultimately, they weren’t giving the community the final say on what would happen at the end of the day.”

Based on these findings, we provide several short- and long-term recommendations focused on improving and eventually diminishing the role of the criminal legal system and its actors in the RJCCs. Our recommendations include but are not limited to prioritizing transparency, accountability, and openness around RJCC operations, service providers, staff, funding, and outcomes in order to effectively implement restorative justice principles; ensuring practitioners receive ongoing, rigorous, community-led restorative justice training; taking steps to improve participant autonomy; improving feedback processes to evaluate the RJCCs; and more. Some of our particularly important recommendations include:

- The Circuit Court of Cook County should immediately implement a community oversight model and pause any future development of additional RJCCs until that has been achieved. The Circuit Court of Cook County has recently announced the opening of its first suburban RJCC in Sauk Village, but we urge caution until more community oversight by residents who practice restorative justice in and belong to the communities from which many RJCC participants hail is prioritized. Improving community oversight and engagement might result in collaboration that leads to creative solutions that address the deeply entrenched systemic problems that cause harm and violence in Cook County communities. Until a community oversight model can be established, we do not believe that new RJCCs should be created.

- We recommend that the Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office create an internal rule to ensure that all accused people eligible for the RJCCs, which are not bound by any statutory framework, are given the automatic opportunity to participate. We recommend that the CCSAO take steps to limit the discretion individual prosecutors have in allowing people to participate in the Restorative Justice Community Courts. Because some court stakeholders may not “buy in” to the RJCC model, these limitations are important to ensure individuals’ biases do not influence this process in ways that hurt some prospective participants’ chances of engagement in the RJCCs. Ideally, any and all people who meet the eligibility criteria to participate in the RJCCs should be automatically, informed of this option by their lawyer, and given adequate opportunity to decide if they would like to participate. Instead of requiring eligible accused people to be selectively invited into RJCCs, they should be included automatically and given the option to opt out in favor of the traditional criminal legal process.

- It’s essential that the Restorative Justice Community Courts become accessible to people accused of offenses that are considered “violent.” The RJCCs currently only accept people accused of nonviolent, first-time offenses. As discussed in this report, the majority of participants in the RJCCs were referred for gun and drug possession crimes. In contrast to the traditional criminal legal system, restorative justice models are uniquely well-equipped to address instances where harm has been done to another person or persons; we find that the RJCC model is inappropriately limited when it includes only participants who have not been accused of such crimes. In many instances, it seems the RJCCs are overseeing cases that would be better handled by dismissing them from traditional prosecution at the outset and referring them to community-based supportive programs. Low-level possession charges, for example, should be diverted out of the criminal legal system altogether. Without expanding eligibility to “violent” allegations, there’s a risk that the RJCCs are, in fact, acting as net-widening programs instead of reducing the footprint of the legal system.

There’s no doubt that the Restorative Justice Community Courts reduce some harms of the traditional system, but our research found numerous tensions between the tenets of restorative justice practice and the structures and processes of the criminal legal system. As one court actor we interviewed noted: “There are three elements of [RJCC]. There’s the restorative justice element of it, the community element of it, and the court element of it. All three of those are constantly in conflict.” This constant conflict is made apparent in our report. Despite the benefits of diversion from the criminal system, without community oversight and resolution of other tensions between restorative justice and implicitly coercive diversion initiatives, RJCCs are simply neighborhood-based courts relying on some restorative practices.

To read our full report, Restorative Justice, Community, and the Courts: An Analysis of the Impact, Benefits, and Elements “Constantly in Conflict” in Chicago’s Restorative Justice Community Courts click here. You can find the Executive Summary here.

Join us on Monday, February 26 at 12:00 PM or 4:00 PM for a webinar to discuss our research process, findings, and recommendations for the future improvement of the RJCCs. Click here to register!